The Article Tells The Story of:

- The Console That Made Home Gaming a Thing: How the Atari 2600 transformed living rooms into arcades.

- Racing the Beam and Beating the Odds: Why Atari’s hardware forced developers into a coding challenge unlike any other.

- The Rise, the Crash, and the Comeback: How bad games, big mistakes, and bold ideas shaped Atari’s fate.

Atari’s Rise: When Gaming Moved Into Living Rooms

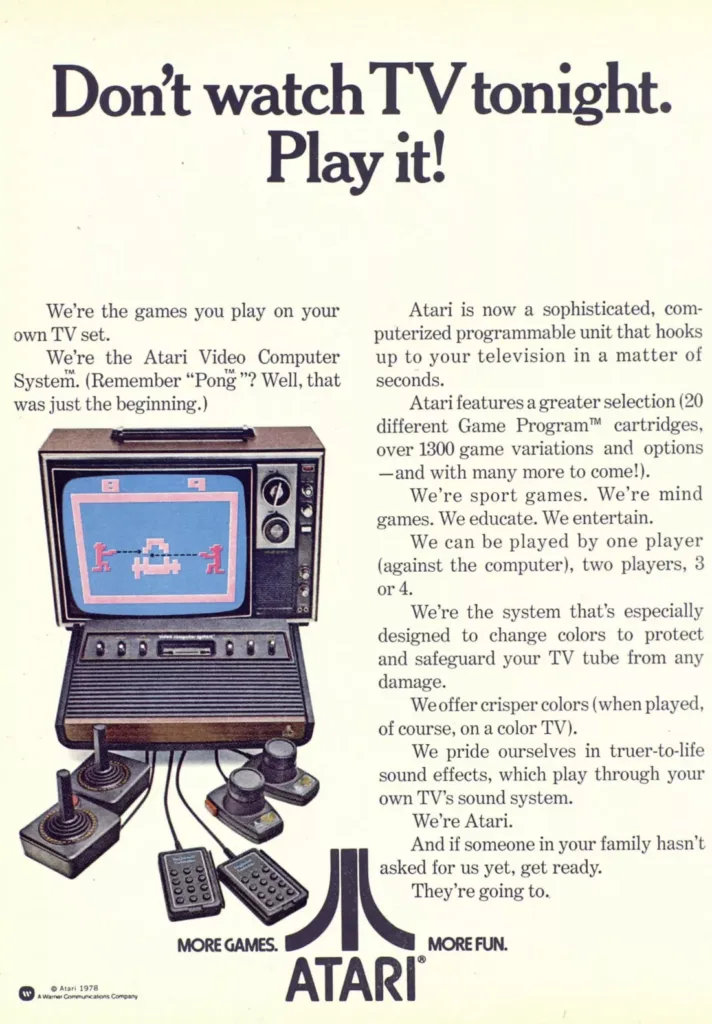

In the late 1970s, the Atari 2600 helped bring arcade-style gaming into homes. After its success with Pong, Atari launched a new kind of system. Instead of using hardwired circuits, the Atari 2600 used a programmable CPU and swappable game cartridges. That made it one of the first consoles to support a library of games, rather than just one.

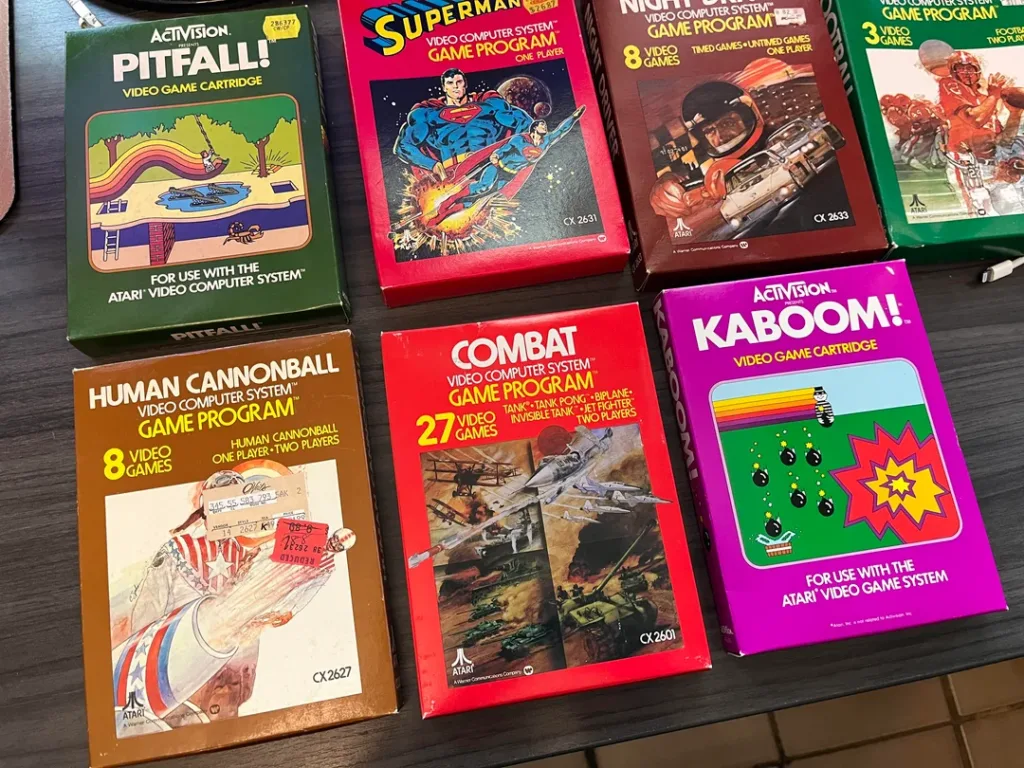

The console was first known as the Video Computer System (VCS) and launched in 1977 for $190—about $1,000 today. It came with one joystick and two paddle controllers. The early game library was small, and its pack-in title, Combat, didn’t impress most buyers.

Things changed in 1980. That’s when Atari released Space Invaders, the first licensed arcade port for home play. The game was simple but addictive. Sales of the 2600 exploded. People bought the console just to play that game. It sold over six million copies and helped Atari grow into a $2 billion business.

Read More About Our Article of Nintendo Switch 2 Revealed: What We Know So Far Published on January 18, 2025 SquaredTech

Hardware Limits Forced Creative Solutions

The 2600’s technology was limited. It had only 128 bytes of RAM. That’s not a typo. It couldn’t store a full screen’s worth of graphics in memory. So developers had to write games that built each line of the screen in real time—at the exact moment it was being displayed on the TV.

This trick, called “racing the beam,” required perfect timing. If the code was off by even a microsecond, the image would break.

Atari hired Jay Miner to design the console’s graphics chip, the Television Interface Adaptor (TIA). It allowed for 160 pixels per line and a maximum of four colors. Instead of redrawing the whole screen at once, the console sent pixel data line by line to match how CRT TVs drew images. That’s why so many Atari games have a blocky, mirrored look—because it was faster and cheaper to repeat one half of the screen on the other.

Read More About Our Article of AMD’s Most Powerful Gaming Tablet Could Debut Soon Published on December 20, 2024 SquaredTech

Inside Atari’s Wild Culture

Warner Communications bought Atari in 1976 and helped speed up development. As the company grew, so did its reputation for chaos. Atari’s office stories included hot tubs, poker games, and open drug use. Founder Nolan Bushnell once had a hot tub installed on-site.

Despite the party atmosphere, the company kept making hit games. But developers were frustrated. Atari didn’t give credit or royalties to the people who created its biggest titles.

One developer, Warren Robinett, pushed back. In his 1980 game Adventure, he hid a secret message that read “Created by Warren Robinett.” It was invisible to most players unless they stumbled upon a hidden room. This was the first known “Easter egg” in video game history.

Rather than remove the message, Atari embraced it. Soon, other developers began hiding surprises in their games too.

Activision: The Breakaway That Changed Everything

Four Atari programmers—David Crane, Alan Miller, Bob Whitehead, and Larry Kaplan—were responsible for 60% of Atari’s sales. But they were uncredited and underpaid. After the CEO dismissed their request for royalties, the group left Atari and started their own company.

They called it Activision. Their idea was simple: give developers credit and a share of the profits. Their first big hit was Pitfall!, a side-scrolling platformer that used clever programming to simulate large levels with limited memory.

Activision’s games sold well. That success led Atari to sue, but the case was settled after two years. The settlement allowed Activision to pay royalties to Atari, setting a new standard for third-party game publishing.

Trouble Starts with Pac-Man and E.T.

Atari’s biggest mistake was overconfidence. In 1982, it released a home version of Pac-Man for the 2600. It became the new pack-in game, replacing Combat. But the game looked bad, played worse, and sounded nothing like the arcade hit. The ghosts flickered. There was only one maze. Critics and players were disappointed.

Then came E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Warner paid millions for the rights. Developer Howard Scott Warshaw had just five weeks to create it. The result was a game that required the manual to understand and frustrated players with its poor collision detection.

Atari made 5 million cartridges. Most were returned. Rumors spread that the company buried unsold copies in a landfill. In 2014, a dig confirmed the story—E.T., Pac-Man, and other titles were found buried in New Mexico.

The disaster hurt Atari’s image and sales. In 1983, the company lost $538 million—after making $300 million the year before.

The 5200 Misstep and the 7800 Delay

Atari released a new console, the 5200, in 1982. It wasn’t compatible with 2600 games. Its analog joystick didn’t return to center, making games harder to control. It was discontinued in 1984.

That same year, Warner sold Atari’s home console division to Jack Tramiel, the former CEO of Commodore. He canceled the launch of the 7800, thinking dedicated consoles were outdated.

Meanwhile, Nintendo released the FamiCom in Japan and brought it to the U.S. as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in 1985. Nintendo avoided the word “console” and used a lockout chip to control which games could be released. This helped avoid the flood of low-quality games that had hurt Atari.

Atari finally released the 7800 in 1986. It could play 2600 games but used the same old sound chip, making its audio feel dated.

The Final Years of the 2600

Atari launched a cheaper redesign called the 2600 Jr. in the late 1980s. It sold for just $50. By this time, Nintendo and Sega were dominating the market. In 1991, Atari pulled the plug on the 2600, ending its run after more than a decade. It had sold over 30 million units.

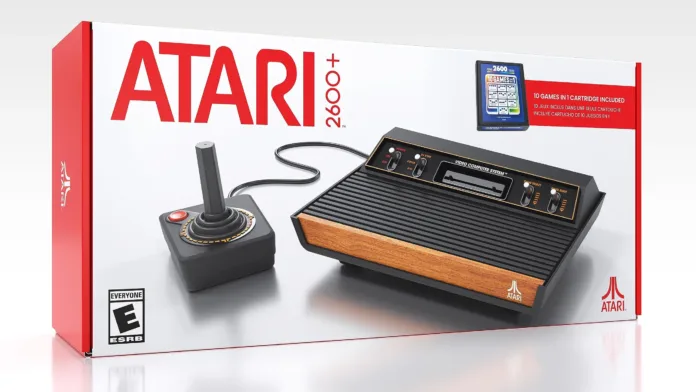

Modern versions have followed. The Atari VCS (2021) came with 100 built-in games. In 2023 and 2024, the Atari 2600+ and 7800+ were released, with support for old cartridges.

Why the Atari 2600 Still Matters

The Atari 2600 showed the world what video games could be. It proved that people wanted to play at home, not just in arcades. It created the first wave of gaming hits and inspired future developers. It made space for third-party publishers. And even in failure, it taught the industry what not to do.

Today’s gaming consoles are closer to gaming PCs than toys. But many still remember the joy of plugging in a cartridge, flipping a switch, and playing instantly.

No updates. No downloads. Just games.